Tomato plants require a balanced amount of nutrients – including nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, sulfur and essential micronutrients – to ensure strong growth, healthy roots, vigorous flowering and superior fruit yield and quality. Nitrogen promotes foliage and growth, phosphorus supports root establishment and flowering, potassium improves fruit color, flavor and resistance to stress, while calcium prevents disorders such as blossom end rot. Magnesium, sulfur and micronutrients (such as boron, iron, manganese and zinc) are critical for photosynthesis and enzymatic functions. Deficiencies in these nutrients can result in weak plants, poor fruit formation, low yields and various physiological disorders, making proper nutrition essential for optimal tomato production.

Macro-N (nitrogen) deficiency

Nitrogen deficiency in tomatoes first appears as pale green to yellowing of older leaves and progresses upward, while the plant shows poor, thin growth and may develop a purple tinge to the stems and veins. The lower leaves are severely affected and often completely yellow or brown and may drop prematurely, while the entire plant produces fewer and smaller leaves and shows reduced growth vigor. This deficiency limits chlorophyll production and amino acid synthesis, leading to poor vegetative growth and inhibition of cell division, ultimately reducing yield and fruit quality if not corrected.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Macro-P (phosphorus) deficiency

Phosphorus deficiency in tomatoes results in stunted growth, small, stiff leaves, and a spindle-shaped plant. The first symptoms usually appear on older leaves, which can be dark green or have a purple or reddish-purple discoloration—especially on the undersides and veins—often developing into necrotic brown spots. Severely affected plants may show poor root growth, premature leaf and bud drop, and reduced flowering and fruiting, which ultimately leads to poor yield and small, acidic fruit if left untreated. Cool soil temperatures can worsen phosphorus uptake, so deficiencies may be more apparent in early spring or cool conditions.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

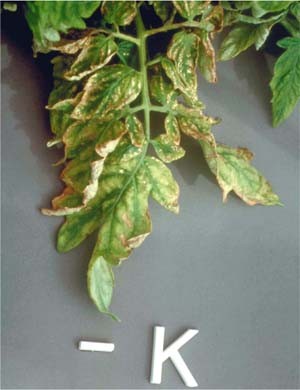

Macro-K (Potassium) deficiency

Potassium deficiency in tomatoes manifests as yellowing and leaf margin scorching in older leaves, progressing to browning, necrotic (dead) spots, and curling, while the veins often remain green. Leaves may be green or tan, wrinkled, and tip scorched, and plants often have thin, woody stems and slow growth. Fruit from potassium-deficient plants can exhibit (“spotted ripening”)—with green or yellow spots, especially around the stem—and may be smaller, softer, hollow, irregularly colored, and have poor flavor and storage quality. Severe deficiency also compromises flowering and fruit set, and increases susceptibility to disease, drought, and cold stress.

|

|

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Secondary macronutrient deficiency – Magnesium (Mg)

Magnesium deficiency in tomatoes usually begins with interveinal chlorosis – yellowing between the veins – in older, lower leaves while the veins remain green and often progresses to light brown necrotic spots and purplish discoloration of the affected areas. Since magnesium is mobile within the plant, deficiency symptoms appear first in older leaves as magnesium is transferred to new growth, leading to leaf yellowing, necrosis, and ultimately leaf loss in severe cases, reducing plant vigor and fruit yield. Excess calcium, potassium, or ammonium in the soil can inhibit magnesium uptake, and this deficiency is common in sandy or washed-out soils and greenhouse environments with heavy fertilization.

|

|

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Secondary macronutrient deficiency – Calcium (Ca)

Calcium deficiency in tomatoes primarily causes a disorder called blossom end rot, which appears as dark, sunken, dry spots on the blossom end (bottom) of the fruit, leading to rotting of the fruit tissue and poor fruit quality. This deficiency usually affects new growth because calcium is immobile in plants and must be continuously supplied through water uptake by the roots. Unstable soil moisture, rapid growth due to high nitrogen, or root damage can exacerbate the problem. Other symptoms include stunted growth, twisted or scorched tips on young leaves, and cracking of fruit if calcium is inadequate during growth. Consistently managing soil moisture and ensuring adequate calcium is available through fertilization will help prevent these problems and support firm, healthy tomatoes with a longer shelf life.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Secondary macronutrient deficiency – sulfur (S)

Sulfur deficiency in tomatoes primarily causes yellowing (chlorosis) of younger leaves, as sulfur is an immobile nutrient in plants. Symptoms include smaller, lighter green plants with chlorosis starting in new leaves, stiffening and curling of young leaves, and sometimes purple or necrotic spots on older leaves. Growth is often stunted with thin, woody stems and possibly delayed maturation. This deficiency is often confused with nitrogen deficiency, but sulfur deficiency symptoms begin in younger leaves rather than older leaves.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Micro-element deficiency – Mn (manganese)

Manganese deficiency in tomatoes causes interveinal chlorosis primarily in younger leaves, in which the tissue between the veins turns yellow to golden while the veins remain green. As the deficiency progresses, brown spots develop in the yellow areas. In some cases, symptoms may also appear on older leaves. A distinctive feature is the presence of yellow or orange-yellow spots and sometimes wrinkling or curling of the leaf tissue near the tips of the shoots. Plant growth is stunted and leaf size is reduced. Manganese deficiency often occurs in soils with high pH, sandy or loamy texture, or during periods of wet, cool weather, and can resemble iron deficiency but with the greener veins seen in manganese deficiency.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Micro-element deficiency – Fe (iron)

Iron deficiency in tomatoes causes interveinal chlorosis in new leaves, where the leaf tissue turns yellow but the veins remain green, leading to stunted growth and reduced plant vigor. This condition is commonly seen in alkaline soils where iron is unavailable despite adequate levels of iron in the soil.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Micro-B (boron) deficiency

Boron deficiency in tomatoes causes terminal chlorosis (yellowing) of young leaves that become small, curled inward, and crooked, while stems become short and thick. Severe deficiencies result in stunted growth, poor fruit formation, and fruits with grooved, corky spots and uneven ripening. Older leaves may turn a yellowish green and petioles become brittle, affecting yield. This deficiency is often caused by sandy or alkaline soils, low organic matter, and unfavorable conditions such as high calcium or nitrogen levels. Correcting a boron deficiency improves cell wall formation, fruit quality, and overall plant growth. Boron should be applied based on soil and tissue tests to avoid toxicity.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Micronutrient deficiency – Zn (zinc)

Zinc deficiency in tomatoes causes dark green leaves with chlorotic (yellow) lightening along the main veins, and the leaf texture appears strong, leathery, and slightly cupped downwards. Affected plants show shortened internodes, resulting in a dense, compact, and stiff growth habit. Early symptoms include interveinal yellowing, especially on younger leaves, which may develop into mottled or tan patterns with severe deficiency. Zinc deficiency often occurs in alkaline soils, high phosphorus soils, or in wet, cool conditions, and disrupts enzyme systems, auxin metabolism, and overall leaf and internodal development, leading to stunted growth and reduced yield.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Deficiency of microelements – Cu (copper)

Copper deficiency in tomatoes causes stunted growth with leaves curling upward and inward, often accompanied by severe leaf edge scorching. Affected leaves turn green-gray, followed by chlorosis (yellowing) and bronzing, eventually turning brown with necrotic margins and black veins. Leaf margins and tips may become wilted or stiff, and leaf number and size are reduced. Poor root development is also common, resulting in stunted plants with sparse foliage and impaired flowering and fruiting. Copper deficiency symptoms are usually seen on older leaves, but in severe cases can also affect younger leaves.

Kimat’s proposed solution: