Macro-N (nitrogen) deficiency

Nitrogen deficiency in citrus causes leaves to turn pale green to yellow, with symptoms beginning on older leaves and progressing to younger leaves as deficiency symptoms become more severe. Older leaves may drop prematurely. New leaves are often small, thin, brittle, and light green. They may darken slightly as they mature but remain less vibrant than healthy foliage. Leaf life is significantly reduced, sometimes from the normal 1 to 3 years to as little as six months. Tree growth is stunted with short, irregular shoot growth and the possibility of branch loss. Nitrogen deficiency results in stunted growth, reduced branch and leaf numbers, reduced flowering, and ultimately reduced fruit yield and quality. Leaf yellowing is usually uniform and does not show the interveinal (between the veins) patterns associated with other nutrient deficiencies such as magnesium or zinc. Leaf veins may appear just slightly lighter than the surrounding tissue or, in some cases, may lean toward white.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Macro-P (phosphorus) deficiency

Phosphorus deficiency in citrus results in a wide range of physiological, morphological and fruit quality problems, primarily due to a lack of phosphorus in the soil, which is essential for plant growth and fruit development. Symptoms usually appear first on older leaves because phosphorus is mobile within the plant. Older leaves lose their dark green color, become small, narrow and turn purple or bronze with a change in color. In severe cases, small bronze-brown freckles may develop, especially along the main veins, which later merge across the leaf blade. Leaves may drop prematurely, resulting in a thinner canopy. Young leaves show a slower growth rate and may also appear short or weak. Fruits are often misshapen, with rough, rough and thick skin and hollow cores, and may fall before normal maturity. The juice content is reduced and the fruit exhibits higher acidity relative to total soluble solids, delaying fruit ripening. The fruit flesh is usually fleshy and has a rough texture with little juice.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

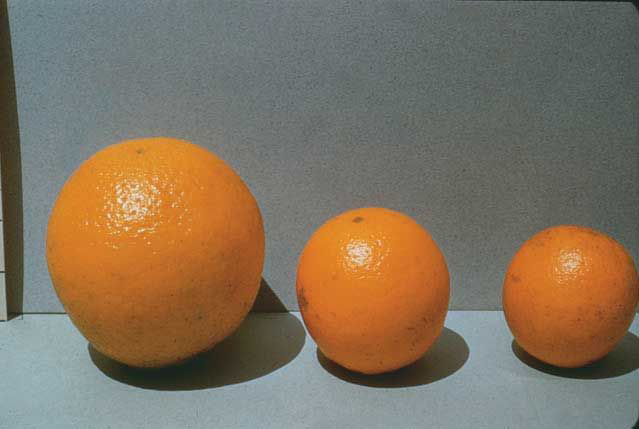

Macro-K (Potassium) deficiency

Potassium deficiency in citrus is mainly observed in older leaves, which develop yellowing or browning at the margins, leaf curling, and increased leaf drop, leading to thinning of the tree crown and wilting of branches. Affected fruits are smaller with thin, smooth skins that easily split or crease, have poor coloration, and are reduced in acidity and vitamin C, leading to reduced marketability and shelf life. The deficiency also slows down overall tree growth, weakens branches, and increases susceptibility to stress, ultimately leading to reduced yield. Potassium deficiency is more likely in sandy or acidic soils, areas with high rainfall or irrigation, and when nitrogen fertilization is preferred over potassium, and is managed through balanced fertilization guided by leaf and soil analyses.

|

|

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Secondary macronutrient deficiency – Calcium (Ca)

Calcium deficiency in citrus causes leaves to become small and thickened with chlorophyll fading along the leaf margins and between the veins, often seen in winter, and may include small necrotic spots. Trees exhibit reduced vigor, thinning of foliage, dieback of branches, and multiple new shoots due to stress. Fruits are typically small, misshapen, with shriveled juice sacs and reduced juice content but higher soluble solids and acids. Calcium deficiency can result in fruit cracking, leathery or shriveled skin, often mistaken for fungal infections, and increased fruit and leaf drop, which reduces overall tree growth and fruit quality. Common causes include acidic, sandy or washed-out soils, drought, and imbalances such as excess nitrogen or potassium. Management includes calcium-rich soil amendments and calcium foliar sprays, especially during critical growth periods or challenging growing conditions. Blossom end rot, a disorder of young fruit with sunken, leathery spots at the blossom end, is a classic symptom directly linked to calcium deficiency and affected calcium transport in the fruit.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Secondary macronutrient deficiency – Magnesium (Mg)

Magnesium deficiency in citrus initially causes interveinal yellowing in older leaves, with this pallor being most noticeable at the tips and margins of the leaves and gradually spreading towards the midrib while the base of the leaves remains mostly green; as the condition progresses, entire leaves may turn yellow or tan, and younger leaves may also be affected, often leading to premature leaf drop, leaf drop, and reduced fruit yield and quality, especially in acidic, sandy soils.

|

|

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Microelement deficiency – Fe (iron)

Iron deficiency in citrus is characterized by yellowing (chlorosis) of the youngest leaves while the veins remain green, a pattern known as interveinal chlorosis. In severe cases, the leaves may turn pale or white, and iron deficiency stunts new growth, causes shoots to wither, and reduces fruit yield. This condition usually occurs in calcareous, high-pH soils where iron is present but unavailable to the plant, and can be worsened by waterlogging or over-irrigation.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Micro-element deficiency – Mn (manganese)

Manganese deficiency in citrus is characterized by yellow-green or yellow spots (mottling) between leaf veins, while the veins and tissue bands on either side remain distinctly green. Young and mature leaves can show this symptom; in mild cases, the mottling pattern often fades as the leaves age, but in severe cases the deficiency persists. Unlike zinc deficiency, manganese deficiency does not reduce leaf size. Severe and persistent deficiency results in reduced growth, poorer yields, and in severe cases, the development of necrotic spots or chlorotic white areas on the leaves. The disease usually occurs in acidic coastal soils low in manganese or in alkaline soils where manganese is present but unavailable due to high pH. Manganese deficiency can be worsened in organic, sandy, high pH, wet, or poorly aerated soils.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Micronutrient deficiency – Zn (zinc)

Zinc deficiency in citrus causes young leaves to be small, abnormally narrow, and compressed on short stems, giving a bushy, stunted appearance. These leaves show chlorosis, or interveinal spots with pale yellow or white areas between the green veins, which continues as they age. Deficiency also results in smaller shoots, multiple buds, and multiple weak branches. Fruits are smaller, pale, coarse, and of poorer quality. Zinc deficiency is common in alkaline or organic soils and is often exacerbated by high phosphate fertilization.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

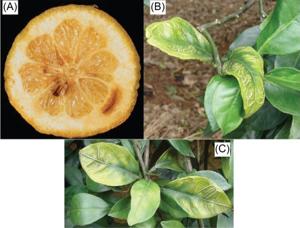

Micronutrient deficiency – B (boron)

Boron deficiency in citrus causes a wide range of leaf and fruit disorders, including deformed and brittle leaves with thick and cracked veins, wilting of the tips of branches, and small, hard, thick-skinned fruits with gummy cavities, low fruit juice content, and poor quality. Boron deficiency causes reduced yield, increased fruit drop, and impaired sugar and vitamin C levels. This problem is common in acidic, sandy, or alkaline soils where boron is leached or unavailable, and is exacerbated by drought or nutrient imbalances. Diagnosis is based on leaf, fruit, and soil analysis.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Secondary macronutrient deficiency – sulfur (S)

Sulfur deficiency in citrus is primarily characterized by pale green to yellow leaves that appear first on younger leaves, unlike nitrogen deficiency which affects older leaves first. Affected trees are stunted and generally have a pale, slender appearance. Chlorosis persists even after nitrogen application, which helps to differentiate sulfur deficiency. Fruit from sulfur-deficient trees is usually small, light green, of poor quality, and delayed in maturity. This deficiency commonly occurs in soils low in sulfur, especially where high-nitrogen fertilizers are used without adequate sulfur supplementation, and in sandy soils with high rainfall where sulfur is easily washed away. Accurate diagnosis relies on tissue examination because visual symptoms can be similar to other nutrient deficiencies. Sulfur is essential for the formation of protein and chlorophyll, so a deficiency impairs photosynthesis and overall plant vigor. In severe cases, trees may experience branch dieback and produce small fruits with poor juice content.

Kimat’s proposed solution:

Microelement deficiency – Copper (Cu)

Copper deficiency in citrus shows several distinctive symptoms, mainly visible on the leaves, shoots and fruit. The leaves become unusually large, dark green and may have a “curved” midrib. The shoots are slender, smooth and angular and often develop clear, blister-like gum sacs or sacs at the nodes, which can develop into reddish-brown gum eruptions. Severe copper deficiency causes young shoots to dry out with the development of numerous buds, known as “witch’s broom”. Fruit symptoms are prominent in oranges, including premature fruit drop, areas of hardened gum with brown spots on the skin (especially on the albedo), cracking of the fruit (sometimes starting at the blossom end and extending throughout the fruit), and darkening of the gum-stained areas, which may become almost black as the fruit matures. Most affected fruits drop prematurely. Copper deficiency is more common in young citrus trees, on sandy, calcareous, organic soils, or where high nitrogen fertilization is applied.

|

|